I’m not sure what it was about my connections with southwest Virginia that in the 1970s sent me fleeing almost as far north as I could go without crossing the border into Canada. I married a Bostonian who is more likely to say “Pahk the cah” than “Bless your heart—you gone park that car or what?” It wasn’t the food that drove me away even though my mother’s delicious fried pork chops and gravy threatened to make me fat. I still like sweet potatoes, albeit not smothered in butter and brown sugar.

But there are aspects I still love about the south—like bourbon.

For a dozen years I taught creative writing at a college in Louisville. During my first semester, I went with some other faculty members one evening to a fancy hotel bar on Fourth Street.

“What should I order?” I asked my colleagues, thinking some sweet southern drink.

“Bourbon,” one said. “It’s required that you drink bourbon in Kentucky.”

When the waitress came to our table, I ordered the only bourbon I knew—Jim Beam.

“We’re out of Jim Beam,” she said.

How could she be out of Jim Beam—wasn’t that a popular brand?

She named an airline whose crew were staying at the hotel. “They were in the bar earlier and drank all the Jim Beam,” she said.

I tried not to look shocked. When I asked what bourbon she recommended instead, she replied, “Woodford Reserve. It’s the official bourbon of the Kentucky Derby.”

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll have a Woodford Reserve. On the rocks.”

The waitress leaned back as if I had struck her.

“I suggest you have the bourbon neat,” she said. “Without ice.”

Drinking bourbon in Kentucky requires a steep and rapid learning curve. It is a sin, I discovered, to dilute good bourbon with ice.

The aroma and taste of bourbon is reminiscent of caramel, and caramel is one southern delight I shall never relinquish.

After one residency, I drove from Louisville east across the Appalachian Mountains to visit an aunt in Southwest Virginia’s Blue Ridge. It’s a six-hour shot along Route 64 through eastern Kentucky and West Virginia to Covington in the George Washington National Forest. During the drive, the only entertainment I could find on the radio was preaching or hymn singing, so I turned it off and rolled down the window to let in mountain breezes. I had called Aunt Hilda, and she made up a bed for me in one of the rooms left vacant after her two grown children moved on. Hilda cooked for me, prayed over me, and coaxed me to church with her on Sunday morning. I was in good hands.

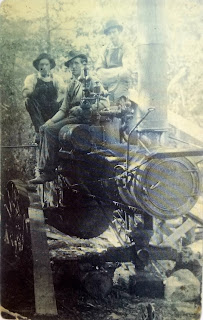

Hilda was in her eighties then. She didn’t offer me a drink other than sweet tea. Her late husband had drunk his fair share of the local moonshine and she had sworn off any alcoholic beverages. But she knew about whiskey and the making of it. She showed me a photo of my great-uncle Bures Paxton sitting on a huge contraption with some of his partners.

“What’s that machinery?” I asked her.

“What’s that machinery?” I asked her.

“It’s a still,” she said. Having lived in Covington all her life, she was able to fill me in on how pervasive the cottage industry was. “Everybody made moonshine.” Her father, grandfather, and ancestors back as far as the Revolutionary War made their own liquor.

They were my people, too.

Many Virginians, she whispered, still engaged in the old tradition of making homemade whiskey. And many of them spent time behind bars rather than give up the business. The moonshine industry sounded like a book, and I started taking notes.

Hot Springs and Moonshine Liquor reaches back to my southern roots by tracing the whiskey trail through my ancestors. From the Revolution to the Civil War, during Prohibition, and as far as the hallowed halls of the U.S. Capitol, illegal liquor involves women whiskey makers, prostitutes, and bootleg drivers as well as blacks and Native Americans. Due out in late 2020, the book can be preordered at https://www.blackrosewriting.com/nonfiction/hotspringsandmoonshineliquor. Use code PREORDER 2020 for a discount.